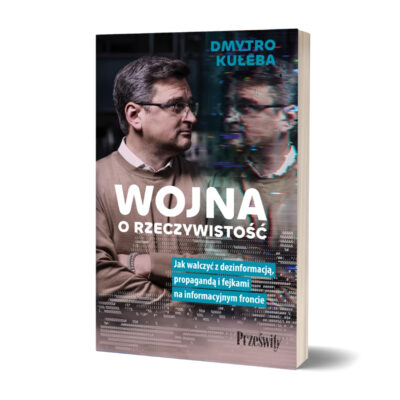

Explore the insightful perspectives of Dmytro Kuleba, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, in a compelling interview focused on international relations and his book ’The War for Reality’. The interview covers topics such as the role of emotions in politics, the nuances of international diplomacy, Ukraine’s diplomatic strategies during the war, and its relationships with countries like Germany and Poland. This conversation offers a deep dive into the intricacies of modern diplomacy and the ongoing battle against misinformation.

Układ Sił: Minister Kuleba, although we have met to discuss your book „The War for Reality”, about the struggle against disinformation and manipulation, I hope that we will also raise current topics in international politics. Let me start by saying that I am delighted with the ease with which your book is read while exploring issues that are often complex and require focus.

Dmytro Kuleba: The greatest challenge for me while working on the book was to keep it simple. I even resorted to a certain writing technique, promising myself to keep the sentences as short and simple as possible and not to use special terminology or words derived from formal language. I have spent a large part of my life working for the government, and that leads to the absorption of a bureaucratic style. I think the language of Polish bureaucrats is also different from the language of people in the streets. So yes, it’s a very complicated subject, but the aim was to structure it and describe it as simply as possible.

In the book, you write about how negative emotions can inhibit us; they cause disappointment and exhaustion. To maintain energy and increase resistance to manipulation, it is important to consciously cultivate positive emotions.

Yes, I can explain this with a recent example. There are emotions disseminated and reinforced by various experts and commentators, saying that our counter-offensive was not as successful as expected. The overall success in the war is questioned. We counter these emotions with the argument that even though the land counter-offensive may not have been as successful as expected, we have pushed Russia back in the Black Sea and restored our export. Russia has no influence on it. We have not allowed it to take over any place in Ukraine. These are the positive emotions we bring to the debate.

But this debate is about negative emotions attacking us and us fighting them with positive emotions. The goal of a communicator should always be balance. The emotion that serves your interests should be the one that attacks, and the emotion that serves the interests of your enemy should be forced to defend itself. This is the key shift we are experiencing. And yes, it is true that people like bad and sad stories.

I feel a spirit of enthusiasm in Kyiv, although people are tired. Has this been achieved through an analogous impact on society?

I think it’s nuanced. People are tired, but they don’t lower their hands because of that fatigue. they understand that they just can’t afford it. We have to win the war. It doesn’t matter whether you are tired or not; you have to keep fighting. You can see the determination of the people to keep fighting. But if you dig into it, you can see that we are all tired and exhausted. We all have a friend or family member who is fighting, who has been wounded, or who has died on the front line. There are air raids every day. This is also the reason why I went so deeply into the subject of this book, because it really needs to be explained to people that there are many layers of perception and emotion that we need to fully understand in order not to fall into the trap of a particular negative vision.

Basically, when I was writing this book, I imagined my reader as a soldier conscripted voluntarily or against his will and sent into battle. My task was to train that soldier to the extent that he would survive and win in that battle. This book was written before the large-scale invasion began. But this is the image I still had in my mind. A soldier who comes from civilian life, wants to defend his country and is sent into battle, and I have to train him to prepare him for that.

And these types of methods seem to work.

Yes. But the reason is that we in Ukraine understand what the game is about. The reason why Poles support Ukrainians is also because they understand what the game is about. But we have to meet different people, and they need explanations, arguments and reasons why they should support Ukraine. it’s not that they don’t sympathize with Ukraine. They definitely have positive emotions about it as a country under attack and defending itself, but they don’t fully understand what is at stake. For people in Ukraine, fatigue is not an excuse to lay down their arms and raise their hands before the enemy. They know that the enemy will probably not even take them as prisoners of war, but will shoot them on the spot in the trench because they do not respect international humanitarian law. This is how it works in the trenches and exactly how it works on social media.

For people in Ukraine, fatigue is not an excuse to lay down their arms and raise their hands before the enemy. They know that the enemy will probably not even take them as prisoners of war, but will shoot them on the spot in the trench because they do not respect international humanitarian law.

On social media and on the internet, the messages you direct to your own public are mixed with some of the diplomatic work of shaping public opinion abroad to gain understanding and support. It seems to be quite a challenge?

Always be mindful of the audience to whom you are speaking. Remember that your words are not exactly what people hear because any piece of information that comes from one mind goes through the filters of our beliefs and our emotions before it settles in other minds. Also, you never know when or how your words might resonate. You cannot be 100 percent sterile in your communication.

Let me give a simple example. Two months ago, I was in Germany, giving an interview to a leading German newspaper and addressing the German public and the German political class as the target audience through the newspaper. I had them in mind when I spoke to the journalist because the main topic of the interview was to explain to the Germans why it was important to deliver air defense systems to Ukraine as soon as possible before the onset of winter. I explained this point. Thinking it was a strong argument, I said: „The Ukrainians are preparing for the worst winter ever”.

Yes, I have read it. In Poland, this quote also appeared.

You see, this has even reached Poland. I left after the interview without even noticing that there was something special about it. But within 24 or 48 hours someone in Ukraine read this interview, took just one line from it about Ukrainians preparing for the worst winter ever. This sentence was literally everywhere, in all media, on every Telegram channel. People obviously did not like this information. The good news is that I reached a huge audience in Ukraine. Even housewives and grandmothers read the excerpt because I was even quoted by newspapers such as the Garden Guide, which usually publishes texts about plants and agriculture. Do I regret having said that? No, because I was speaking to an entirely different audience. If I had not been so sincere, I might not have achieved my goal. But I could not have predicted that it would resonate so much. Just one sentence from an interview published in Germany will have an impact in Ukraine, but also in Poland.

This leads to another problem. Every time you conduct diplomacy with Germany, you speak to Germans, in Poland these messages resonate and are perceived as 'betrayal’ by a part of polish society that is convinced that Poland, not Germany, should be Ukraine’s best friend, and that you are talking behind our backs to the Germans.

Well, Ukraine and Poland have a very similar history of relations with Germany. Let’s put it this way: our historical wounds related to Germany are very similar, and therefore we can understand each other’s problems with regard to these relations. But that is why, I think, at least in part, Poland is so sensitive about the issue of Ukrainian-German relations. I remember that as part of the election campaign in Germany, someone from Poland tweeted, and it became quite a popular narrative in your media, that Ukraine and Germany were plotting against the Polish government or something like that. The people who did that knew what resonated with the perception of Poles, and they didn’t care whether it was true or not. It was two hundred percent fake news, but they did it anyway; they included it in the discussion because they used it. They knew it would resonate with the Poles. Both Ukrainians and Poles need to understand one thing. We need Germany as a big player in Europe, and we need to be sure that Germany will never again do to us what it did centuries ago, which we still remember. Decades and centuries ago. The best we can do is not to be jealous, but to agree that both our countries need Germany in a mutually respectful relationship. We need them.

We need Germany as a big player in Europe, and we need to be sure that Germany will never again do to us what it did centuries ago, which we still remember. Decades and centuries ago. The best we can do is not to be jealous, but to agree that both our countries need Germany in a mutually respectful relationship. We need them.

Let us look at the last European Council meeting, where the decision was taken to start accession talks with Ukraine. Poland fought like a lion. The Baltic States and many others fought against the Hungarian veto. In the end, however, we needed Germany to make the move. We all need them. My final point is that it took some time for Germany to really change its views on Eastern and Central Europe in light of such a large-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. But what Germany has been doing in recent months in terms of support for Ukraine is worth recalling, and we should stick to the facts on this issue.

In short, I believe that Poles and Ukrainians should reconcile over Germany and accept the wounds of the past. We all want to prevent them from happening again in the future. Therefore, there should be no jealousy or bad feelings towards us or you because of the cooperation with Germany, as long as we understand that we need Germany for the sake of Europe and our common security. Poland and Ukraine, on the other hand, are and should be strategic partners.

What do you have in mind?

I think that what we should talk about, what we should already start thinking about, is a Ukrainian-Polish alliance within the European Union. Because we will be two very strong players. We will make Poland stronger, and Poland will make us stronger. We should not play the game of balancing ourselves with the Franco-German alliance or any other alliance in Europe. We should start a real conversation about how we are going to solve the bilateral problems on the road to the European Union because what is happening now with these trucks and grain exports is disappointing. It shouldn’t be happening, but we need to find ways and mechanisms to prevent it. The deeper we get into the accession talks, the more such issues will come up from different sides. Poles and Ukrainians must prevent such situations from turning into problems and resolve them quickly and amicably, since we have already failed to prevent them from occurring. Secondly, we need to start talking about what we are going to do together in the European Union. What will be our contribution to shaping Europe? Because when enlargement happens, both the Western Balkans and the whole of Eastern Europe will be part of the same political project, the European political project, except for Belarus. For the first time in history, the whole of Europe, from Lisbon to Kyiv, will live as one. Ukrainians and Poles will be part of this great project and will have a role to play. This is the kind of strategic discussion and partnership that I believe we must seek.

These crises you speak of and the accusations of mutual betrayal are probably a good way of dividing us and keeping us out of the alliance.

That is exactly my point. Only when we are together are we strong.

There are quite a few countries that do not care about this.

But this is not the kind of relationship that Ukrainians and Poles should allow any third party to change or influence, whether it is Berlin, Stockholm, I don’t know what else, Budapest, or Paris. It doesn’t matter which country it will be. But you are right. I think the Ukrainian-Polish alliance inside the EU will make not just one, but many capitals, think about how to prevent it or how to balance it. Part of the answer to this question will come in the reform of the European Union itself. But this is a battle you will be fighting. Poland should always remember that whatever short-term difficulties your companies may face with Ukraine’s entry into the European Union, the political and economic benefits of Ukraine’s membership in the Union and sitting at the same table with you will largely outweigh such problems. This is what real strategic dialogue means: thinking not only about tomorrow but also about the future while solving the problems of today.

This is what real strategic dialogue means: thinking not only about tomorrow but also about the future while solving the problems of today.

In the book, you write that the feeling of betrayal is one of the strongest feelings. It festers easily, so how do you deal with it?

There are two ways. The first is not to turn the question of supporting Ukraine into a matter of internal political debate. Let us simply not do that. A politician from one faction may say: 'We can fight for everything in this country, starting with taxes and ending with subsidies, but it is in our strategic interest to support Ukraine’. It helps a lot when we stop feeding fears and bad emotions with daily news.

And secondly, it is necessary to respond unconditionally and swiftly to any operation such as influencing public opinion by false polls that try to sow divisions among us. Sometimes politicians make a mistake when a certain negative narrative is implanted in public opinion. Let’s say that in Poland some journalist, expert or account on X publishes a conspiracy theory about Ukraine having betrayed Poland. How should the Polish authorities react to this? Sometimes you should not react because you will only publicize the news. Let it die on its own. But if the issue is already reaching the point where we are talking about it in an interview, then it has probably become huge and should not be ignored. That means you have to go out and very openly, very directly, talk to your own public and say that the truth is different, that this is not true. Then I would ask opinion leaders to reinforce that message. These techniques are basic, but the main thing is to talk to people. You should not sit back and wait for the problem to resolve itself and for people to forget about it. Why is this issue being presented in terms of betrayal without any real basis? Because, as I said, betrayal, the feeling of being betrayed is a very strong one.

According to you, these feelings are huge in Ukrainian society.

Yes, absolutely.

Who will betray you? What does the public think? Who? The Americans?

The point I make in the book, and it is a principle I live by, is that only Ukrainian citizens themselves can betray the Ukrainian nation. The problem of the sense of betrayal has reached such a level in Ukrainian public discourse that in my book I even seriously suggest that the word should be deleted from our everyday vocabulary; not from the Ukrainian vocabulary as such. The word zrada (зрада) sounds the same in Polish?

Yes, zdrada, betrayal.

The word zrada… The whole discourse in Ukraine was structured…. There is less of that now, by the way, slightly less. But this is a disease and this disease has not been treated well. It can reappear. For some time, the whole debate in Ukraine was organized between two poles: zrada and peremoha (перемога) – betrayal and victory. Everything was labelled either as a betrayal or as a victory, which leads to the radicalization of society in both ways because you either look only for victories and do not accept anything less than that, or you label everything as a betrayal, and the strength of this feeling forces you to react radically against anyone associated with this betrayal.

It’s like a swing. You, me or a child sits on the swing and we start swinging. We try to see how high we can swing. However, if we swing too high both ways, the chance of us falling and breaking our necks increases exponentially. This is what happens to a society that starts to think of itself and everything that happens in the world in terms of black and white, or betrayal and victory. No one can betray us except ourselves. And I’m glad that with the onset of large-scale invasion, this dichotomy has become less dominant and less damaging. But it has not healed; it has not disappeared. It is simply suppressed now by a widespread sense of the need to fight the enemy. When the war is over, we will again throw ourselves into this fight.

The same thing is happening in Poland…

You see. Because human beings, and this is the point of this book, are the same everywhere. Our brains work in the same way regardless of the language we speak or the color of our hair or skin. We are human beings. When politicians want to heat up public opinion or manipulate it, they always appeal to emotions. This is why I say that politicians in Ukraine and Poland should not do anything that inflames negative emotions in the Ukrainian and Polish societies against each other.

The answer is probably nurture, from a very young child shaping a mature person.

Yes. We are products of our past, of everything we have lived through, the conversations we had with our parents, the stories our teachers told us at school, the lectures we listened to at university, the relationships we had in the past. Everything we know about the world—our perception of the world—is a product of our past. So it all really does matter.

But most importantly — and this is what you write about in the book — are values. Values protect us from extremes?

Yes.

And how to reconcile values with diplomacy, with realism in international relations? There are countries like China that do not share democratic and liberal values.

In 2014, the Ukrainian Revolution of Dignity swept away the previous government, the pro-Russian government, and basically swept away a class of politicians, those Ukrainian politicians whose values were very different from those of the people who stood on the Maidan and defended democracy and human rights in Ukraine. The government changed and a very intelligent man came along who knew foreign affairs and who had been to the Maidan, as I had. He came to me and said: „Dmytro, this is an opportunity for Ukraine to finally start building a foreign policy based solely on respect for human rights. This revolution was about dignity, about human rights. Now we have to subordinate our entire foreign policy to the priority of defending human rights in the world, and everything will become much easier for me, for us.” I said to him: 'What you are saying sounds very encouraging, but for a country to afford to make human rights alone the fundamental principle of its foreign policy, it must be rich, secure from external threats and politically stable for at least a few decades, with a more or less homogeneous society. Then one can understand foreign policy so very narrowly’. This is not the case with Ukraine. Values are what holds us together. Without values, people and states are just pieces of garbage. Seriously. Both people and states need values.

Values are what holds us together. Without values, people and states are just pieces of garbage. Seriously. Both people and states need values.

However, being guided solely by one’s own values, without taking into account the realities of the world, would lead both people and states into very dire situations. The struggle that a values-driven diplomat has to undertake on a daily basis is to decide how to balance his or her values with national interests. How to protect and advance national interests vis-à-vis countries that do not share the same set of values, while at the same time not abandoning one’s own values or crossing red lines derived from them. This is what is called the art of diplomacy. You need principles, you need values, but you have to be aware of the fact that you live in a world where sometimes you cannot afford to stick to them fully.

Our famous football club, Dynamo Kyiv, had the most famous coach, Valery Lobanovsky, who took Dynamo to the heights in Europe in the 1970s and 1980s and then in the late 1990s. He was a genius of football strategy. He once said the words that I, as a football fan, still remember and apply to my work. He said this: „We don’t betray our rules, but we keep improving them, so stick to the rules, but live in the real world”. This fits our Ukrainian reality. If I were a tiny island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean or a very rich, small country in Europe, perhaps I would think differently. But my challenge is always to defend my values with due regard to the most pragmatic national interests of my country.

So, do you think Ukraine will strengthen relations with China?

We are pursuing a more dynamic relationship with China. We believe they are a player that can play a role in restoring peace in Ukraine. But we are establishing this dialogue as a Western country, a country belonging to the West. This is where the part about values comes in. One could be Lithuania, for example, which said: „We don’t need China. Now we will only talk to Taiwan’. Or you can be like France, which is definitely a European nation with values, but very open to dealing with China. The same countries will share the same values but have two completely different policies.

My final question concerns the Americans who will elect a new president in 2024. Do you think that after the election, the support from the United States will still be as it is now?

Historically, Democrats in the US have been less willing to fight Russia, but we are fortunate that there is President Biden who is a Democrat and understands Ukraine. He understands what is at stake, and he is doing very, very much to help us. Not only to us, but to the world that the United States represents. On the other hand, historically, Republicans have always been more willing to fight Russia, and the tendency to be more forceful and assertive in foreign policy is still very much present in the Republican Party. However, we have a potential Republican candidate, Mr Trump, who has different views on relations with Ukraine and Russia. My point is not to oversimplify the situation, either for the Democrats, for the Republicans or in the context of the United States as a whole. Because ultimately, the point is that there is much more at stake in Ukraine than just Ukraine itself. Helping Ukraine is in the best strategic interest of the United States. We will prevail regardless of the party affiliation of the next American president.

Thank you very much for the interview.

Thank you.

interviewed by Paweł Ziorko,

editor-in-chief Uklad Sil