While diplomatic headlines tend to overshadow military news, many scenarios are circulating, evoking the deployment of troops in Ukraine in the event of a negotiated settlement of the conflict or even a simple truce. While some statements are part of political posturing or strategic signaling, it is nevertheless undeniable that a planning phase has begun in many countries, as demonstrated by the Paris staff meeting of March the 10th, to explore the political and capacity issues of a stabilization force generation for Ukraine. The equation can be summed up very simply: whatever the scenario, there must first be a strong political will, then a clear mission, and finally a credible force, capable of carrying out the second for the benefit of the first.

As for now, the peaceful deployment of foreign forces in Ukraine seems impossible without a ceasefire and the approval or at least the nihil obstat of both warring parties. This last point is subject of seemingly irreconcilable postures: Ukraine only envisions the deployment of forces from countries willing to provide a defensive security guarantee, while Donald Trump mentioned the possibility of „peacekeeping forces” and Vladimir Putin still does not want to hear about European troops in Ukraine, perceived as indissolubly linked to NATO, which he loathes. The hypotheses can therefore be reduced to two scenarios: the deployment of troops from states favorable to the provision of security guarantees to Ukraine on the one hand and the deployment of a simple „interposition” force on the other. In both cases, geographical and technical constraints specific to the conflict will weigh on the conceivable formats, complicating the equation. Thus, while the hypothesis of an interposition force from non-European countries under a UN mandate seems both unfavorable to the security of Ukraine and very improbable, the political and military conditions which could allow the deployment of European forces are very complex and deserve to be studied, which is the purpose of this article.

Geographic determinants: towards a DMZ?

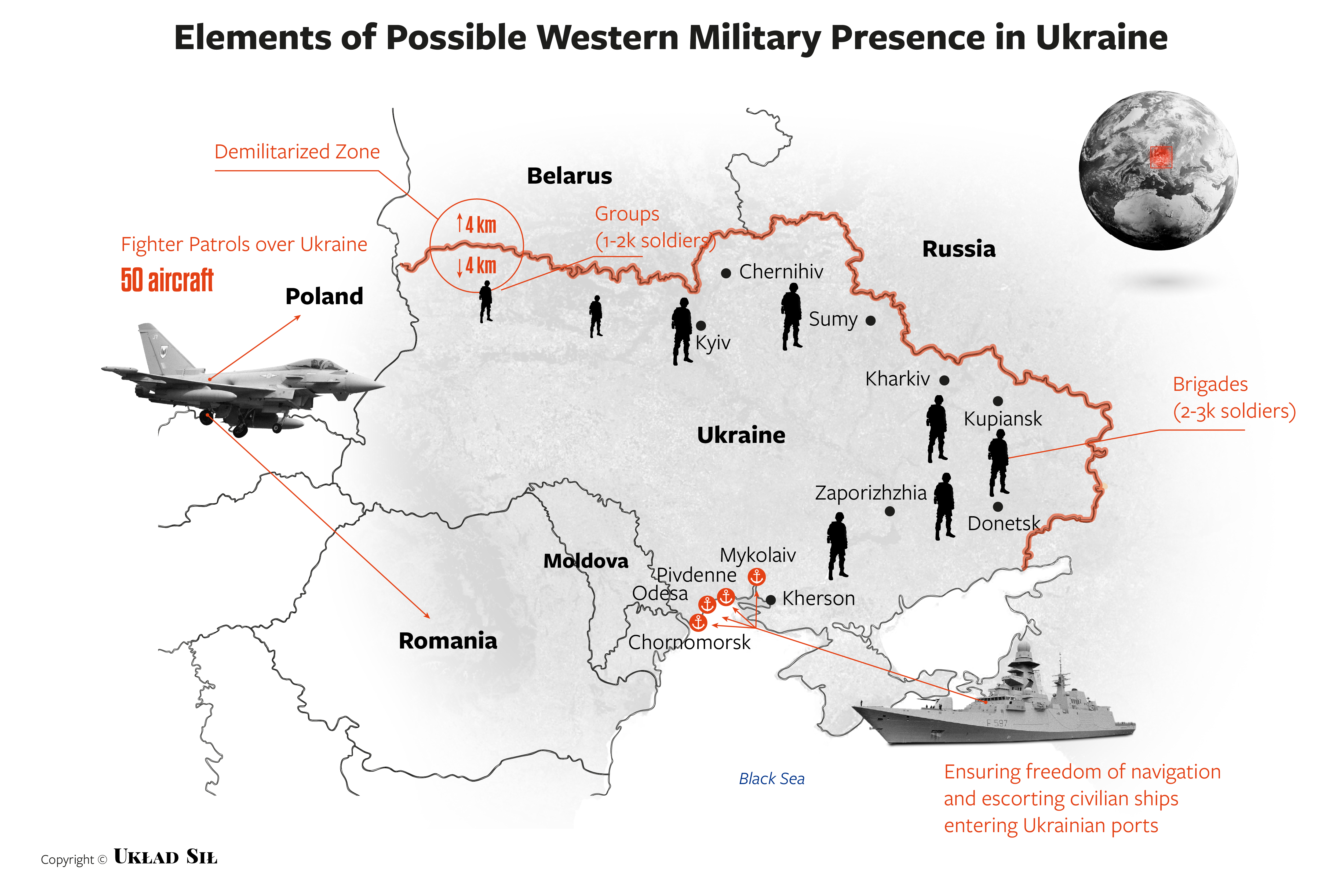

In all conceivable hypotheses, it seems unlikely that the Russian and Ukrainian armies would be able to maintain lasting contact in the event of a ceasefire. The experience of the Minsk II agreements and the repeated violations of the ceasefire by pro-Russian separatists suggest that a frozen situation “within gunshot range” is not conceivable if the ambition is to stabilize the conflict in the medium term. The difficulty of attributing certain acts of violation of the ceasefire on the ground in a context of intensive use of mines and drones and the extreme tension that would reign as soon as the fighting ceases would therefore probably imply the withdrawal of each party on both sides of a large demilitarized zone (DMZ) whose depth would exceed the range of the most common weapons. As a reminder, the DMZ in Korea extends approximately 4km on each side of the border, forming a strip 8 to 10km wide. Based on the length of the current front line (about 1,300 km), this would represent more than 10,400 km² in Ukraine which would thus be „emptied” of all human occupation. That being said, it must be considered that the entire length of the border with Russia (or even with Belarus) will have to be covered if Ukraine is to be guaranteed against a renewed Russian offensive. This point considerably extends the line to be monitored and could represent a DMZ of more than 2,000, or even 3,000 km long, including the Belarusian border, and this, by „drawing straight” and excluding the border irregularities. Ukraine being a large country, the foreign forces stationed there should be able to quickly project capabilities to any point of the DMZ. This suggests a decentralized system, with several local battle groups spread across the territory. As an indication, NATO’s reassurance forces in the Baltic countries must cover a thousand kilometers of border, again by „drawing straight”. To do this, the Alliance deploys approximately 10,000 men.

Ukrainian security by Ukraine first

Before considering the format of foreign forces in Ukraine, it must be remembered that the country’s security will rest first and foremost on its own army. Covering a 2,000 km long front against the Russian army’s possible return is only possible if Ukraine maintains a significant number of men under the flag, in a high state of readiness, well armed, supplied and dug-in with in-depth defensive positions. However even assuming that Russia does obtain the demilitarization of its neighbor and that Ukraine maintains a sovereign army of a size not limited by a treaty, the imperatives of reconstruction and economic recovery, as well as humanitarian imperatives, will involve the gradual demobilization of a large part of Ukrainian soldiers and the reduction of the number of active brigades, very soon after any ceasefire. In South Korea, again for comparison, there are some 450,000 South Korean soldiers facing the North Korean army, supported by 20,000 American soldiers located less than 100 km from the DMZ. While surveillance by drones and early warning aircrafts, mining and fortifications may limit the need for personnel, operational mobility constraints will remain for combat groups: the Ukrainian army probably can’t afford to align less than a brigade of 3,000 men every 20 or 30 km, which would require maintaining 200,000 to 300,000 men in active duty, not counting reserves and support. It therefore seems unlikely that Ukraine will be able to demobilize more than half of its army, although this figure could be reduced depending on the possible involvement of states prepared to provide security guarantees. Enter the (other) Europeans.

The “Euro-Atlantic” hypothesis

This is the most favorable hypothesis for Ukraine. In this scenario, a group of countries from the Euro-Atlantic area (including Canada) would agree to deploy military forces in Ukraine on a prolonged basis after a possible ceasefire. It’s important to keep the term “European area” as it would ideally involve countries from all across Europe, members or not or EU or NATO, forming a “coalition of the willing”. This is the hypothesis currently promoted by France and the United Kingdom. The political objective would be to guarantee the security of Ukraine and deter any Russian offensive return. The first question, that of political will, would therefore be inextricably linked to an explicit commitment to engage combat against Russia if Vladimir Putin renews his aggression. This is the sine qua non condition of deterrence: to be ready to fight. As for Ukraine, in return for renouncing a resumption of hostilities on its side to recover by force lost territories, the country would be protected by the presence of these troops belonging to a group of countries that are, if not allies, at least friends and partners.

In this hypothesis, European troops would mainly be deployed in the second echelon, less than 100km from the DMZ. In order to be able to provide effective reinforcement of the Ukrainian army while being capable of autonomous operations, these forces should be organized into autonomous combat groups. Two to three combined arms tactical battalions would form the backbone of a combined arms brigade of about 2,000 to 3,000 men, modeled on the NATO forces deployed in the Baltic countries. Considering that the Dnieper constitutes a barrier reducing the need for cover forces, it would nevertheless be necessary to have a brigade in the area between Kherson and Zaporizhia, with detachments covering the coastline around Mykolaïv. Another brigade would be deployed between Zaporizhia and Donetsk, a third between Donetsk and the Kupiansk region, a fourth south of Kharkiv, a fifth between Sumy and Chernihiv and necessarily a sixth in Kyiv, intended to protect the political capital and its institutions from any coup de force. By adding two other smaller groups (1,000 to 2,000 men), which could cover the Belarusian border, this Euro-Atlantic force would imply the deployment of between 14,000 to 22,000 men in Ukraine. Even if the deployment of forces could be done at a good distance from the DMZ, it also seems essential to engage the reassurance forces in patrols along the Ukrainian line, in order to make any Russian attack more „dangerous” because it could at any time put the lives of European soldiers at risk. The central idea remains to deter, here by “random presence of trigger forces anywhere in the DMZ”. And yet these are only ground forces divided into combat groups, without logistics, without air support and without mobile reserves.

The air component would be crucial both to ensure situational awareness and to discourage Russian in-depth strikes. It would also, in case of ceasefire violation, provide support to both European forces and the Ukrainian army. Thus, the force must be able to muster round-the-clock Airborne Early Warning (AEW) cover, daily satellite imagery, solid data fusion and sound theater missile defense, integrated with the Ukrainian air defense system. A permanent fighter-bomber force will have to be setup in Poland or Romania, with nearly permanent combat air patrols over Ukraine. Of course, this would severely strain the potential of European air forces and require the commitment of a sizable share of European aircrafts, probably around 50 in forward presence with perhaps double the number available in home countries on short notice. At sea, a truce should allow the Europeans to obtain from Turkey the right to enter the Black Sea. Allied naval forces should conduct Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS) as soon as possible, while escorting civilian shipping in and out of Ukrainian waters and contributing to demining. Here again, the idea is to provide trigger forces to deter Russian aggression while enhancing the radar coverage and air defense of coastal areas.

Even considering that most of the air support could come from neighboring European countries, given the length of the zone to be covered and the road distances, it therefore seems unlikely that a credible force could have fewer than 20,000 and more likely (at the beginning) 30,000 men boots on the ground, in Ukraine. A presence which, like the Korean DMZ or the Lebanese UNIFIL, could last several decades, with a need for permanent rotation, meaning the long time commitment of three times that actual number. Yes, the Europeans must be ready to “put 100,000 men” for Ukraine. In terms of capabilities, such a hypothesis would nevertheless have the merit of making it possible to lighten part of the Alliance’s presence in neighboring countries, particularly in Slovakia, Hungary and Bulgaria. The Russian presence in Transnistria, Belarus and Kaliningrad would, on the other hand, prevent a reduction in the effort in Romania, Poland or the Baltic countries. But not all the countries currently participating in the NATO reassurance forces would be willing and/or in capacity to deploy in Ukraine, where the stakes are higher than anywhere else.

In effect, in terms of quality, the reassurance forces will have to be credible according to the mission entrusted to them: deterring Russia by being really ready to fight. Beyond raw numbers, there is thus a paramount challenge in terms of capabilities. To fulfill the mission the idea is not to rely on slow moving heavy combat forces that could be too slow to react to limited attacks and vulnerable to concentrated fires, but rather on light, reactive forces, with good mobility potential. Forces that could move quickly to any point of the DMZ, while targeting Russian aggressors with long range weapons. These forces should have anti-aircraft and electronic warfare capacities, numerous FPV drones and loitering munitions and be supported by engineers to quickly perform counter-mobility actions (anti vehicles mines), dug positions or clear passage routes. Nimble and fast, those brigades would strike hard, supported by western air power, while avoiding being trapped into protracted fights. However, few armies in Europe are able to deploy such units today. Assembling a common force will necessarily be done by relying on NATO structures. France, the UK, Germany, Poland and the Scandinavian countries seem to be the most obvious candidates to provide the core of the five brigades that would be deployed along the front line. Specifically for the deterrent aspect, it seems absolutely essential to ensure the participation of one or better of the two European nuclear powers, France and the United Kingdom, which would offer a guarantee against Russian nuclear blackmail. The sixth brigade protecting Kyiv would be multinational, and less prepared European nations could either come in as reinforcements within these units, handle less risky sectors (along the Dnieper) or help secure the border with Belarus.

But when it comes to mobilizing the structures of the Atlantic Alliance, the Trump administration’s attitude remains the final difficulty for the Europeans. On the one hand, the United Kingdom seems politically disinclined to engage on the ground in Ukraine if it does not have an American “backstop” guarantee. On the other hand, the American role as a framework nation within NATO is difficult to replace and most European armies – like the Polish army – are largely built as capability bricks that must be integrated into the structures of the Alliance dominated by American command and control means, lacking a true national capacity to wage a full-fledged conflict alone. In NATO, the Europeans tend to have the muscles, while the Americans provide the skeleton and most of the sinews. The road to emancipation is long for the Europeans, but the deadlines are short. It is necessary for European countries to think of effective joint command architecture and if possible, given recent events, detached as much as possible from American dependencies. This is going well beyond the original defense missions of the EU. However, European countries have a lot of staff officers and some states, like France, have a long experience of multinational forces deployed far from home.

As we can see, the stakes of the constitution of this European force in Ukraine are similar to those of European rearmament in general, which is a good thing: everything that is done for the defense of European space will be good for Ukrainian security and vice versa. Proof, if any were needed, of Ukraine’s belonging to European democratic space.

Conclusion: what path for a European force in Ukraine?

As we can see, the challenges of a Euro-Atlantic or strictly European hypothesis in Ukraine are numerous and such a deployment would represent, in the long term, a complex and costly commitment for the nations of the old continent. But it is on the political level that it remains the most difficult to consider today. After all, in terms of deterrence, nuclear or conventional, everything is played out in the heads of the leaders. What matters is that at some point the Europeans are able to deter Putin from renewing aggression. Articulating political will and armed force remains the most important issue. In this respect, it must be admitted that it is unlikely that Russia will accept a European force immediately, while acknowledging that the Europeans are not inherently militarily weak. Two paths exist, one short and the other longer. In the short path, the Europeans would dare to enter Ukraine without Russia’s agreement. This would be the application of the „careless pedestrian” strategy. As soon as a truce is concluded, Ukraine would call European forces to its territory, which would enter very quickly to deploy behind the front line, as “trigger forces”. The European capitals involved, unanimously, would warn Russia that any resumption of hostilities on its part would see them ready to engage defensively in Ukraine, on the ground, in the air and in its territorial waters. There is of course a risk that Vladimir Putin will refuse such an intrusion and decide to resume hostilities. An immediate „last warning” would then be launched through strikes, if possible in territory internationally recognized as Ukrainian, which would hit Russian forces there. Combined with diplomatic pressure and the promise of lifting sanctions in the event of Russian compliance with the ceasefire, this attitude would in fact have every chance of working, Vladimir Putin having demonstrated in the past that he did not wish to engage in direct combat against the Western powers. A phase of strategic signaling – possibly with nuclear options – would follow, and Russia would find a way to “back down and explain it is still victory”. That is the way dictatorships work.

In the second, longer path, the Europeans would increase their support for Ukraine while standing aside and continuing to offer their interposition force, in order to force Russia to assume the political cost of refusing the ceasefire. This seems to be the current dominant hypothesis, which places the harsh reality of the fighting on the Ukrainian army alone. The rationale is that Russia will end up wearing itself out by 2025, to the point where its economy and its armed forces will no longer be able to support an offensive attitude. Russia would be forced to accept a lasting pause through exhaustion, which would allow the negotiated entry of European troops in Ukraine. However, this current European attitude, a mixture of military wait-and-see and economic and political support, could be considerably „strengthened” by the effective preparation of a force that could be deployed quickly on the one hand and by the political assertion that there are extreme circumstances that could lead to its deployment without prior ceasefire – in the event of Ukrainian army rout, power-grid collapse, excessive humanitarian suffering or an attempt to destabilize the country through political assassinations for example. Deterrence remains a complex process to understand and it is built on the perception of a firm attitude and credible capabilities by the adversary that one wishes to deter. It is therefore up to Europeans who want to help Ukraine to learn to assert themselves through words and actions, even before being able to enter the country. The most crucial argument to endorse this new European assertiveness being that the safeguard of Ukraine is the safeguard of all Europe. And we must remember the words of Raymond Aron in 1939: “I also believe in the final victory of democracies, but on one condition, that they want to be victorious”.

Stéphane Audrand